Imagine standing on a vast stretch of land lined with thin silvery-green leafed trees swaying in the warm air of the desert. The fruit feels familiar, a green globose berry– is it karonda? You pluck this mysterious yet familiar fruit and bravely bite into it. Shockingly bitter, almost unidentifiable, this is an olive – far away from the land of gelato, pesto, hummus, or La Tomatina.

The olive cultivation project in India was first conceived in 1996 when experts visited Israel to study the crop. However, it only came to fruition in May 2006 when the then CM of Rajasthan, visited Israel to attend the 16th International Agriculture Conference. During her visit, she noticed similarities in the climate of the two regions – the presence of desert terrains in both and the absence of a specific cash-crop in one. The team met with the Indian Council of Agriculture with the proposal of growing olives in Rajasthan, but were denied on the basis of past failures in a similar project (growing olives in collaboration with the Italian government) in Himachal Pradesh in 1985.

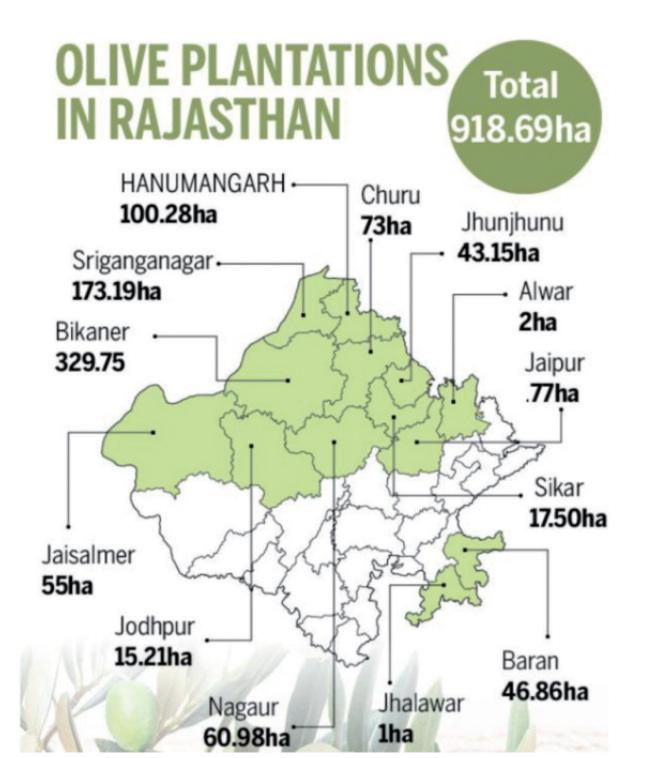

This case, however, was touted to be unique. In 2007, a tripartite agreement was signed between The Rajasthan State Agricultural Marketing Board, Israel based Indolive Limited and Pune-based Plastro Plasson Industries India (now Finolex Plasson Industry) to form Rajasthan Olive Cultivation Limited ( ROCL) in the same year. The project heavily relied on the expertise of the parties in the Joint Venture. Indolive had successfully cultivated olives in Southern Israel, Finolex specialized in the latest technology for drip irrigation and the State Agri Board came with a deep understanding of the agro-climatic conditions of the region.The next steps were quick. Almost 1.12 lacs were imported from Israel from March 2008 to September 2009 and planted on 182 hectares of land with different agro-climatic regions of the state – Sriganganagar, Nagaur, Bikaner, Jalore, Jhunjhunu, Alwar and Jaipur. The first plants were planted at Bassi, Jaipur. After the cuttings grew into small plants, they were transplanted in different regions.

The goal of importing the olive plant from Israel was to give farmers an incentive to grow this cash crop and earn from this liquid gold. An olive tree, which costs INR 130 was available at INR 28 with an addition of 90% of the cost of setting up drip irrigation. An attractive 3-year plan at the time, took more time to bear fruit.

The trees start bearing fruits in 2012, a year or two after they should have — only in Bikaner, Sriganganagar and Naguar out of the seven areas.Following this glimmer of success in some areas, farmers and farm owners adopted some saplings. It was only in 2014, that some areas of the state saw decent production.

The ambitious goal of the project became elusive. Even though olive is a hardy plant, one that can withstand high-temperatures and drought, the necessary condition for the plant to bear fruit is highly specific - a chilling temperature. After the lack of fruiting in other areas in 2015, the government of Rajasthan looked at alternate ways to use the olive trees - olive leaf tree was one such path. “Farmers ने जिस उम्मीद से लगाया था, fruit निकला नहीं ,” said Manoj Singh Dewal, the manager at Olive Development at ROCL. The production of olive leaf trees is a project undertaken by private companies in partnership with the government.

In the last few years, the project has somewhat been stagnant - the surprising bumper crop hasn’t seen good markets, large stretches of olive trees lie fruitless and the promise of any kind of gold (liquid or not) remains unfulfilled.The proposition of olives in Rajasthan almost defies common sense in an obvious way. Why would one import a non-native species, which is already growing in large parts of the world both successfully and unsuccessfully, into a new environment? To become self-sufficient, to capitalize on the world’s obsession with olive oil or to provide farmers an alternate way to earn? There are no easy answers when there’s stress on the farmers to earn their livelihood, and stress on the land to grow and grow more food. What also rings true is the lack of awareness of the world moving towards growing the same things in different regions. As if the world’s lands are up for monoculture. Ecologist Debal Deb also pointed out that the success of olive plantation will be at the cost of the local flora. The cost of altering the ecology of a region must be considered. The decision on “What to grow?” has never been more complicated, especially now when we are dealing with the aftermath of climate change.

I visited the Rajasthan Olive Cultivation Ltd. at Bassi in Dec 2023 and stood in the middle of a 2 acre land of olive trees all around me. It was unfamiliar, strange and breathtaking. I left empty-handed.

And that’s everything for this week.

dhoop is an independently published magazine, so producing and selling the print versions of the magazine is the only way to share our work. However, through this series of ‘Some dhoop for you!’ newsletters, we want to come to your inbox and share some insightful, fun, and meandering thoughts on the discourse around the different elements that make dhoop. If you learned anything new, the best way to support us and this newsletter is to share it far and wide.